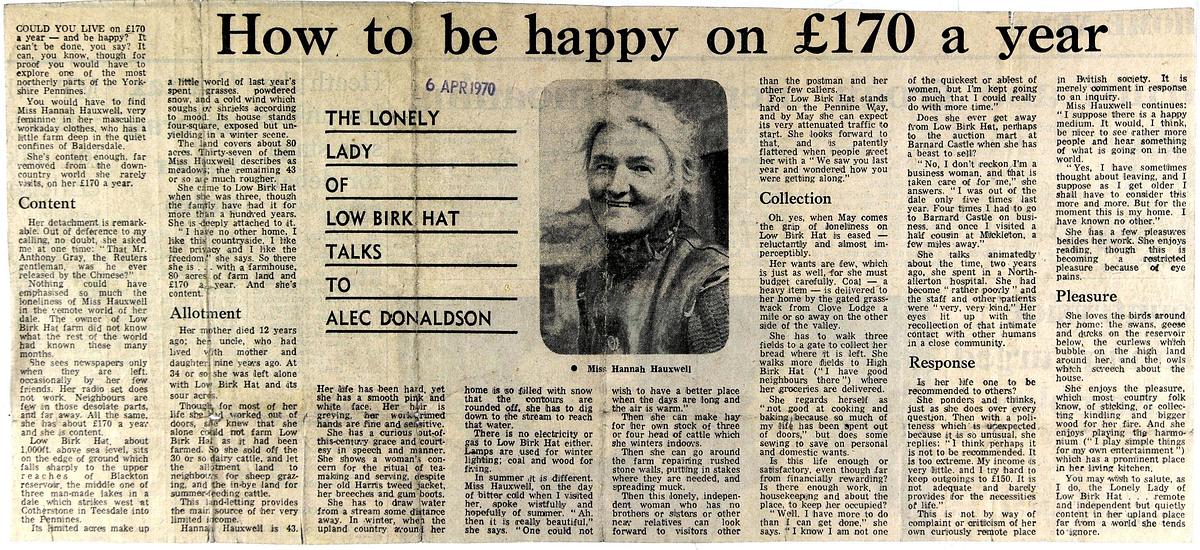

Television viewers were captivated by their first glimpse of Hannah Hauxwell and her isolated homestead, Low Birk Hatt Farm in the North Pennines.

They were stunned to learn how she lived without electricity, running water and regular human contact, drinking from a stream and collecting bread deliveries from a field several miles away. To them, her world, lit by oil lamps, was a quaint and sobering throwback to the hard lives endured by generations of Dales farmers until the Second World War.

Yet the war had finished decades earlier, and Hannah was still living alone on her remote smallholding where little had changed since the 19th century.

She remained there until 1988, when failing health persuaded her to sell up and retire. She died in a nursing home in 2018, and her passing prompted an outpouring of nostalgia about her incredible life and the Yorkshire Television documentaries which turned her into an unlikely celebrity with fans all over the world.

Hannah's life was austere and often primitive, but today her choices seem in many ways to have been ahead of her time - she was an independent woman who never felt the need to marry or depend on a man for income, companionship or social status.

She was self-sufficient decades before environmental concerns became popular, living frugally and sustainably with few material possessions and little waste. She was keenly aware of the mental peace and stability brought by her self-imposed solitude, shunning television and other modern technology and unintentionally espousing the benefits of 'off-grid' living.

Hannah is the subject of Facebook appreciation groups and her fans still eagerly consume the dwindling number of news articles about her posthumous legacy - the auction of her hand-stitched quilts, the exhibition of her personal letters and photographs, the sale of the cottage where she spent her latter years.

She has become synonymous with Baldersdale, the village closest to her farm, and the wider Teesdale area - formerly in the North Riding of Yorkshire, it became part of County Durham during an administrative reorganisation in the 1970s.

She was also perhaps the last of her generation of hardy Pennine hill farmers, impervious to the harsh weather conditions, isolation and a lack of comforts. Many of their old smallholdings - including Hannah's - have been renovated by urban families moving into the area not to work the land but to appreciate its natural beauty.

So what legacy has Hannah left behind?

'Too Long a Winter'

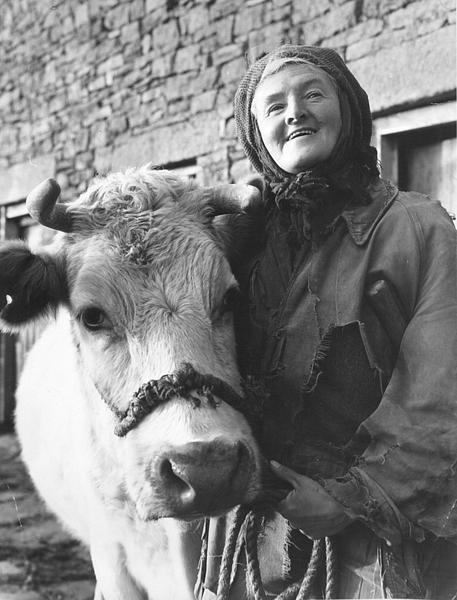

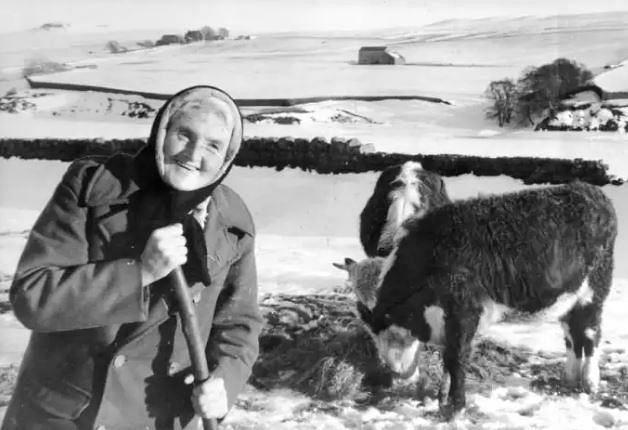

Hannah first came to the attention of the media in 1970, when the Yorkshire Post interviewed her about her meagre yearly budget of less than £200.

She didn't feel she was entitled to or even needed electricity or running water, and seemed content tending to her cattle in knee-high snow. She had worked the farm alone since the death of her mother and uncle when she was 34.

Three years later, television crews arrived in her lonely dale to film Too Long a Winter.

The national reaction to Hannah was something of a watershed moment. Materialistic 1970s Britain - land of motorways, supermarkets, pop music, the first wave of cheap foreign package holidays - woke up to the fact that there were still people living spartan, Victorian lives in a forgotten wilderness.

Not only that, but they were charmed by her wholesome nature. The television critic Sean Day-Lewis spoke next day of her “extraordinary dignity, simplicity and acceptance” which, he said, “shone without a hint of acting or editorial manipulation”.

Viewers contacted ITV offering to help Hannah - a helicopter had to be hired to fly food parcels and gifts to Low Birk Hatt. Money was raised to connect her farm to a power supply.

With hindsight this seems ironic, almost an attempt to impose modernity on someone who had rejected consumerism. But they were well-meaning and wished to alleviate the harsher privations she suffered during six months of the year.

She eagerly accepted the invitations that came her way, visiting the Savoy in London and even travelling abroad for the first time.

By the 1980s, however, Hannah was struggling with the physical demands of sustaining her existence. She made the difficult decision to sell up and retire to a cottage in nearby Cotherstone.

New beginnings

It was 1988 when Robin and Ann Dant were handed the keys to 'the most famous farmhouse in the world'.

Hannah Hauxwell, then 62, had entrusted Low Birk Hatt Farm to them. They had bought a property that was cold, damp and had no telephone line or plumbing.

The couple were looking to move from the Yarm area and met Hannah when she showed them around, her pride evident.

“We knew we had found what we had been looking for,” said Ann.

It took the Dants seven years to renovate the dilapidated farmhouse.

“It is not as isolated as it looks on the films. I would say it is secluded as there are other properties in the dale,” said Robin, a former potato procurement manager for a crisp firm and a gifted DIY’er who did most of the work himself at the weekends and during holidays.

He and Ann, a retired nurse, replaced the track with a new road and installed a borehole, septic tank and central heating. They also converted the old dairy and pantry into a utility room, the stable into a kitchen and the loft into a bedroom and office space.

A new garden room overlooks the fells, meadows and reservoir and altogether there are five bedrooms and three bathrooms, all with breathtaking views. The dining room was once Hannah's kitchen.

The property’s many period features include the old hooks that the Hauxwells used for hanging meat. There are some in the sitting room, which Hannah revealed was “only ever used for funerals and pig killings”.

That was in the days before fridges when farmers took it in turns to slaughter and divvy up a pig. Outside, Robin and Ann renovated the outbuildings, planted trees and made a garden overlooking their 15 acres.

Their love for Low Birk Hatt grew stronger.

“The countryside is so beautiful and peaceful. There is no traffic noise and no light pollution and when the moon is full, its reflection on the reservoir is a spectacular sight. The promise of spring is announced by the call of the curlew, a sound I will always associate with this place,” said Ann.

It is a paradise that still holds a lot of potential. The halfway point of the Pennine Way is on the doorstep and the restored barn next to the house and the field barn at the top of the field could make perfect walkers’ accommodation.

In 2016, the Dants too decided to move on.

“We can fully understand Hannah’s reticence to leave Low Birk Hatt. It is such a beautiful place but we are leaving for the same reasons she did. We are getting older and it is time to move on,” added Robin.

The farmhouse and land went on the market for £590,000. Hannah was invited to visit by the Dants but never did, preferring to remember her home as it had been.

An inventory of a life

"This is what made Hannah" says volunteer Cath Maddison, as she contemplates the bin sacks full of belongings salvaged from a garage rented by Hannah Hauxwell.

Cath recites an incredible list of items - the collection dates back to Hannah's great-grandparents' era and includes:

- school exercise books

- ration coupons

- wartime ID cards

- her mother's gas mask

- records of loans

- 150 funeral invitations

- wedding cards

- minutes from 1930s council meetings

- unopened fan mail

- an invitation to a Buckingham Palace garden party

- annotated scripts for books about her life

- smallpox vaccination forms dating from the 1800s

- a list of local families who had applied for post-war council housing.

The 'treasure trove' of letters, photographs, invitations, birthday cards and innumerable other miscellaneous items has taken curators of the Fitzhugh Library, a charity dedicated to the preservation of historic records, months to sort through.

The correspondence donated by the executor of Hannah's will provides a facinating insight into a vanished way of life.

Cath is keen to stress that the collection, which will form part of an exhibition that will launch at the library's Middleton-in-Teesdale home in September, is not just about Hannah, but a snapshot of rural social history in its own right.

"It is wonderful heritage - it's not just Hannah, it's what came before Hannah. We've had a lot of interest already since announcing the exhibition on our Facebook page - we hope we have enough volunteers on the day it opens!

"We really want it to re-awaken interest in Hannah and also widen interest in the history of local farming communities - the letters highlight how little transport there was and the sort of health problems they had. It's a vast resource and a reminder of just how much the world has moved on. Hannah saved it all and it's what made her really."

Honouring Hannah's legacy

With her global appeal and the continuing interest in her life, it seems that there is potential for Hannah to be commemorated with a permanent memorial or a focal point for visitors.

The main site of pilgrimage is Hannah's Meadow, a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest reclaimed from land that was once part of her 80-acre farm.

Hannah deployed traditional farming methods, and as a result the meadow is one of the best-preserved in the Pennines. She never re-seeded the fields or used artificial fertilisers, and today rare species of flower flourish.

The land was purchased in 1988 by the Durham Wildlife Trust, who still manage it. An outbuilding was converted into an unmanned visitor centre.

Another stop on the Hauxwell trail is the Bowes Museum, in her birthplace of Barnard Castle.

Soon to go on display at the museum - itself housed in an architecturally stunning building - is a quilt stitched by Hannah's grandmother, which went up for auction after her death. It's currently undergoing conservation work.

Curators were delighted that a private buyer donated the rare textile - a total of 13 of Hannah's quilts were sold.

The nearby village of Cotherstone also has significance to Hannah's fans, as it was the location of her retirement cottage, which went on the market for £160,000 after her death.

She moved to a care home in West Auckland in 2016 but did not sell the property during her lifetime.

She was delighted with Bellview Cottage's indoor bathroom and central heating - but later admitted to never using the washing machine.

It was in a garage across the road that the lifelong hoarder's stacks of personal belongings were discovered and subsequently bequeathed to the Fitzhugh Library.

Hannah's devotees have even suggested that blue plaques are erected by her former homes to mark the lasting impact of a unique character whose life and values still resonate with us today.

Cath Maddison points out regretfully that Barnard Castle and the Teesdale area lacks local museums - the magnificent Bowes focuses on fine arts rather than heritage - which makes it difficult to organise accessible exhibitions about the woman who put England’s ‘last wilderness’ on the map.

Today, Hannah’s fans can follow in her footsteps, walking the streets and lanes she once used, enjoying the tranquility of the fields she once owned.

One suspects humble Hannah Hauxwell would not have wanted any fuss made - yet her memory lives on, and she has preserved the memories of others for generations to come.

You may also be interested in:

Yorkshire farmer Hannah Hauxwell’s retirement cottage up for sale

WATCH: The bleak 1970s documentary that turned Hannah Hauxwell into a household name

True daughter of the Dales: Inside story of how Hannah Hauxwell’s lonely life moved the nation